Anyway, without further ado here's my list. As in previous years, this is not a 1 to 10 ranking: the books below are merely listed in the order in which I read them.

56. December 30. The Stag Head Spoke, by Erina Harris. 91 pps.

55. December 27. Cipher, by John Jantunen. 299 pps.

54. December 22. [Sharps], by Stevie Howell. 87 pps.

53. December 17. Invasive Species, by Claire Caldwell. 69 pps.

52. December 15. The Zone of Interest, by Martin Amis. 306 pps.

51. December 5. The Betrayers, by David Bezmozgis. 225 pps.

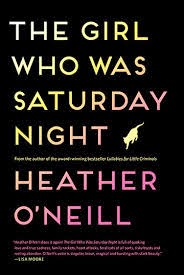

50. November 29. The Girl Who Was Saturday Night, by Heather O'Neill. 403 pps.

49. November 17. All Saints, by K.D. Miller. 222 pps.

48. November 6. The Green Hotel, by Jesse Gilmour. 112 pps. (For review in Quill & Quire.)

47. November 4. The Eve of St Venus, by Anthony Burgess. 122 pps.

46. October 30. FreeFall magazine Volume XXIV No. 3 (Fall 2014). 106 pps.

45. October 28. CNQ 90 (Summer 2014). 80 pps.

44. October 20. Four English Comedies, edited by J.M. Morrell. 414 pps.

43. October 9. Paths of Desire, by Emmanuel Katton (translated by Kathryn Gabinet-Kroo). 175 pps. (For review in Quill and Quire.)

42. October 4. The Walking Tanteek, by Jane Woods. 446 pps.

41. [September 17. The Secrets Men Keep proofs. 178 pps.]

40. September 9. Stowaways, by Ariel Gordon. 95 pps.

39. September 5. Play: Poems about Childhood, the Kid Series: Volume One, edited by Shane Neilson. 81 pps.

38. September 3. The Search for Heinrich Schlögel, by Martha Baillie. 261 pps. (For review in Quill and Quire.)

37. August 26. Sweetland, by Michael Crummey. 322 pps. (For review in Canadian Notes and Queries.)

36. August 16. Leaving Tomorrow, by David Bergen. 277 pps. (For review in The Winnipeg Review.)

35. August 8. The Antigonish Review 177 (Spring 2014). 144 pps.

34. August 2. Look Who's Morphing, by Tom Cho. 126 pps.

33. July 29. Everyone Is CO2, by David James Brock. 63 pps.

32. July 26. All My Puny Sorrows, by Miriam Toews. 321 pps.

31. July 14. How Does a Single Blade of Grass Thank the Sun?, by Doretta Lau. 119 pps.

30. July 9. Prism International, Spring 2014. 85 pps.

29. July 7. Prairie Ostrich, by Tamai Kobayashi. 200 pps.

28. July 1. Sons and Fathers, by Daniel Goodwin. 230 pps. (For review in Quill & Quire)

27. June 25. He'll, by Nathan Dueck. 94 pps.

26. June 23. Anthony Burgess, by Roger Lewis. 470 pps.

25. June 14. Emberton, by Peter Norman. 295 pps. (For review in The Winnipeg Review.)

24. May 26. The Fiddlehead No. 259, Spring 2014. 119 pps.

23. May 20. CNQ 89 (the Montreal issue). 80 pps.

22. May 17. Career Limiting Moves, by Zachariah Wells. 331 pps.

21. May 8. This Location of Unknown Possibilities, by Brett Josef Grubisic, 342 pps.

20. April 27. More to Keep Us Warm, by Jacob Scheier. 79 pps.

19. April 24. The Age, by Nancy Lee. 281 pps.

18. April 14. David Foster Wallace Ruined My Suicide and Other Stories, by D.D. Miller. 246 pps. (For review in Quill & Quire)

17. April 7. The Strangers' Gallery, by Paul Bowdring. 349 pps. (For review in The Fiddlehead)

16. March 25. The Bear, by Claire Cameron. 221 pps.

15. March 19. Honey for the Bears, by Anthony Burgess. 272 pps.

14. March 11. When Is a Man, by Aaron Shepard, 279 pps. (For review in Quill & Quire.)

13. March 11. From Plato to NATO: The Idea of the West and Its Opponents, by David Gress. 610 pps. (for research)

12. March 3. The Antigonish Review, No. 176 (Winter 2014). 144 pps.

11. February 28. Miracles of Life: Shanghai to Shepperton, by J.G. Ballard. 250 pps. (For possible essay)

10. February 23. The Kindness of Women, by J.G. Ballard. 343 pps. (For possible essay)

9. February 13. Empire of the Sun, by J.G. Ballard. 279 pps. (For possible essay)

8. February 4. Dear Leaves, I Love You All, by Sara Heinonen. 174 pps.

7. February 1. Archive of the Undressed, by Jeanette Lynes. 79 pps.

6. January 29. All the Broken Things, by Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer. 330 pps.

5. January 22. Strip, by Andrew Binks. 281 pps.

4. January 13. Winter Cranes, by Chris Banks. 64 pps.

3. January 11. CNQ 88 (Summer/Fall 2013). 80 pps.

2. January 4. Left for Right, by Glen Downie. 101 pps.

1. January 2. The Art of Sufficient Conclusions, by Sarah Dearing. 222 pps.

55. December 27. Cipher, by John Jantunen. 299 pps.

54. December 22. [Sharps], by Stevie Howell. 87 pps.

53. December 17. Invasive Species, by Claire Caldwell. 69 pps.

52. December 15. The Zone of Interest, by Martin Amis. 306 pps.

51. December 5. The Betrayers, by David Bezmozgis. 225 pps.

50. November 29. The Girl Who Was Saturday Night, by Heather O'Neill. 403 pps.

49. November 17. All Saints, by K.D. Miller. 222 pps.

48. November 6. The Green Hotel, by Jesse Gilmour. 112 pps. (For review in Quill & Quire.)

47. November 4. The Eve of St Venus, by Anthony Burgess. 122 pps.

46. October 30. FreeFall magazine Volume XXIV No. 3 (Fall 2014). 106 pps.

45. October 28. CNQ 90 (Summer 2014). 80 pps.

44. October 20. Four English Comedies, edited by J.M. Morrell. 414 pps.

43. October 9. Paths of Desire, by Emmanuel Katton (translated by Kathryn Gabinet-Kroo). 175 pps. (For review in Quill and Quire.)

42. October 4. The Walking Tanteek, by Jane Woods. 446 pps.

41. [September 17. The Secrets Men Keep proofs. 178 pps.]

40. September 9. Stowaways, by Ariel Gordon. 95 pps.

39. September 5. Play: Poems about Childhood, the Kid Series: Volume One, edited by Shane Neilson. 81 pps.

38. September 3. The Search for Heinrich Schlögel, by Martha Baillie. 261 pps. (For review in Quill and Quire.)

37. August 26. Sweetland, by Michael Crummey. 322 pps. (For review in Canadian Notes and Queries.)

36. August 16. Leaving Tomorrow, by David Bergen. 277 pps. (For review in The Winnipeg Review.)

35. August 8. The Antigonish Review 177 (Spring 2014). 144 pps.

34. August 2. Look Who's Morphing, by Tom Cho. 126 pps.

33. July 29. Everyone Is CO2, by David James Brock. 63 pps.

32. July 26. All My Puny Sorrows, by Miriam Toews. 321 pps.

31. July 14. How Does a Single Blade of Grass Thank the Sun?, by Doretta Lau. 119 pps.

30. July 9. Prism International, Spring 2014. 85 pps.

29. July 7. Prairie Ostrich, by Tamai Kobayashi. 200 pps.

28. July 1. Sons and Fathers, by Daniel Goodwin. 230 pps. (For review in Quill & Quire)

27. June 25. He'll, by Nathan Dueck. 94 pps.

26. June 23. Anthony Burgess, by Roger Lewis. 470 pps.

25. June 14. Emberton, by Peter Norman. 295 pps. (For review in The Winnipeg Review.)

24. May 26. The Fiddlehead No. 259, Spring 2014. 119 pps.

23. May 20. CNQ 89 (the Montreal issue). 80 pps.

22. May 17. Career Limiting Moves, by Zachariah Wells. 331 pps.

21. May 8. This Location of Unknown Possibilities, by Brett Josef Grubisic, 342 pps.

20. April 27. More to Keep Us Warm, by Jacob Scheier. 79 pps.

19. April 24. The Age, by Nancy Lee. 281 pps.

18. April 14. David Foster Wallace Ruined My Suicide and Other Stories, by D.D. Miller. 246 pps. (For review in Quill & Quire)

17. April 7. The Strangers' Gallery, by Paul Bowdring. 349 pps. (For review in The Fiddlehead)

16. March 25. The Bear, by Claire Cameron. 221 pps.

15. March 19. Honey for the Bears, by Anthony Burgess. 272 pps.

14. March 11. When Is a Man, by Aaron Shepard, 279 pps. (For review in Quill & Quire.)

13. March 11. From Plato to NATO: The Idea of the West and Its Opponents, by David Gress. 610 pps. (for research)

12. March 3. The Antigonish Review, No. 176 (Winter 2014). 144 pps.

11. February 28. Miracles of Life: Shanghai to Shepperton, by J.G. Ballard. 250 pps. (For possible essay)

10. February 23. The Kindness of Women, by J.G. Ballard. 343 pps. (For possible essay)

9. February 13. Empire of the Sun, by J.G. Ballard. 279 pps. (For possible essay)

8. February 4. Dear Leaves, I Love You All, by Sara Heinonen. 174 pps.

7. February 1. Archive of the Undressed, by Jeanette Lynes. 79 pps.

6. January 29. All the Broken Things, by Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer. 330 pps.

5. January 22. Strip, by Andrew Binks. 281 pps.

4. January 13. Winter Cranes, by Chris Banks. 64 pps.

3. January 11. CNQ 88 (Summer/Fall 2013). 80 pps.

2. January 4. Left for Right, by Glen Downie. 101 pps.

1. January 2. The Art of Sufficient Conclusions, by Sarah Dearing. 222 pps.